Hidden in Plain Sight

The Indispensable Role of The Social Matchmaker

Revised March 25th 2025

Preface

“We’re matchmakers of a non-romantic kind” says Tom Doody, a longtime practitioner of relationship-building work.

Social matchmakers bridge the social gap between those who move about freely in society and those who are overlooked and disconnected from meaningful relationships.

Take William, who lost his home while in rehab and ended up in a nursing home permanently. If he had a committed friend perhaps they could have helped him return to supported living. Or Sonya, a young woman with developmental disabilities, who moves from one program to another, always a recipient of services but never a valued member of community.

The matchmaker works to change these realities by fostering relationships rooted in shared humanity. They recognize William needs an ally beyond the system and they seek ways for Sonya to connect with at least one friend who values her as a person, not just as a recipient of services.

Yet without recognition or support, these efforts often fade. This role is vital yet remains hidden in plain sight.

People come to the work of matchmaking in many different ways. To illustrate one possible path—and perhaps spark your own imagination—let’s begin with a fictional story.

Note: All names and scenarios in this post are fictional but reflect real-life experiences.

Intersection of Wadsworth Terrace and Fairview Avenue, northern tip of Manhattan.

The Burden

Everyone in Washington Heights knew José.

As a social worker, José spent years navigating the endless bureaucracy of city services. He fought to secure housing placements that took months—sometimes years. He helped clients fill out forms for benefits that barely covered rent. He watched case after case get shuffled through a system that seemed designed to manage poverty rather than alleviate it.

One day, after yet another client told him, “I don’t need another program. I need a friend,” something inside José cracked.

So he left. Not because he didn’t see the value and necessity of social services, but because he saw a crucial gap that needed to be filled. A gap he felt drawn to.

Free from obligations and unsure of what was next, he returned to Emmanuel Heights, the small church he had been part of for years. There, he began meeting with those in need before and after services. He listened. He checked in. He connected where he could.

The Weight

When the congregation took notice, they appointed him to lead the long-dormant Justice & Outreach Program. If someone needed a meal, they asked José what to do. If someone needed a ride to the doctor, they asked José to drive them. If an elderly neighbor was lonely, instead of visiting themselves, they told José about them.

At first, he took pride in the recognition. It felt like his work was making a real difference. But over time, the weight of it all became unbearable. What once felt noble now felt suffocating.

Although his community had entrusted him with overseeing the Justice & Outreach Program, even acknowledging him before the entire congregation during a special Sunday service. However, the leadership offered little guidance or support beyond that public gesture.

He took pride in his respectable role, but in the process, he was losing himself. And his family was growing weary of it.

The Professor’s Wisdom

José reached out to one of his old professors from before his social work days.

Professor Kaufman, now in his seventies, was a retired professor of religion and philosophy.

After walking Mrs. Feldman, an elderly widow from his church, back to her apartment, José headed to the café to meet with Kaufman.

Kaufman noticed the fatigue. “You look burdened.”

José sighed, stirring his coffee. “Honestly, I’m overwhelmed. The more I help, the more people depend solely on me.”

Kaufman said, “Community flourishes when responsibility is shared, not when one person carries it all.”

At first, José felt deflated, hoping to get a compliment from his Professor. He resisted. No one cares as much as I do, he thought. The response was instinctive, almost defensive.

But as he sat with it, something shifted. Maybe he didn’t have to bear the burden alone. Maybe his role wasn’t to carry everyone, but to lead people to a place where they could care for one another.

Feeling humbled—and somehow lighter—he thanked Professor Kaufman.

“Anytime,” Kaufman said.

Shared Responsibility

With a renewed perspective, José felt eager to reconnect with his Justice & Outreach role within the community.

The next time Aaron called about feeling isolated, José didn’t just go visit him. He thought of Daniel, a man in the congregation who had been looking for ways to get involved.

"Daniel, would you be willing to meet Aaron?" José asked. "You both love discussing history. He could use a friend."

The next time Jasmine told him how exhausted she was caring for her daughter alone, José thought of Miriam, a retired teacher who had mentioned wanting to help young families.

"Would you be open to meeting Miriam?" José asked. "She could keep you company, and she loves kids."

At first, people were hesitant. They had expected José to fix it himself.

But something shifted.

Aaron and Daniel became study partners, discussing books over coffee.

Jasmine and Miriam became friends. Miriam would watch Jasmine’s daughter for an hour while they talked, giving Jasmine a rare break.

Not everyone said yes.

But some did. And even those who declined appreciated being asked, often expressing their respect for those who stepped forward.

Emmanuel Heights began to shift. A new culture was forming—one where responsibility was shared, and relationships grew beyond obligation.

José was no longer carrying everything alone.

It didn’t mean every problem was solved. Some people still needed caseworkers, access to benefits, and professional services. But now, they also had genuine relationships.

People weren’t just being helped. They were being seen.

José had finally realized his role wasn’t to solve every problem. It was to be a matchmaker, of a non-romantic kind.

A Hidden Role

José embraced the role, and in many ways, it bore fruit. But his efforts remained ambiguous—not just to others, but to himself.

He endured strange looks as people failed to fully grasp what he was doing or the support he needed, and the diversity he was ushering into the community began receiving mixed reactions. Their perceptions of what he was trying to do confused and discouraged his own perception.

People know what social workers and teachers do, he thought, but what am I doing?

He soon discovered that matchmaking is a deeply complex and multifaceted role.

With a family to support and little recognition or structured community support through a Core Group (reference this post), José knew that once he returned to work, he would have to scale back and the efforts would likely begin to dissipate.

Why This Work Remains Hidden

Throughout history, people have instinctively taken on the role of social matchmakers, often informally, recognizing that structured services alone do not meet relational needs.

In Jewish tradition, for example, Levites helped sustain communal life, and in the Christian tradition, deacons ensured that widows and the poor were not neglected. The Friendly Visitors of the 19th century—an early form of social work—sought to foster personal relationships with marginalized people, though their work often reinforced class divides.

Today, governments recognize social isolation as a public health crisis, leading to roles like Link Workers in Social Prescribing models and Ministers for Loneliness in the UK and Japan. These roles address isolation through community connections and policy changes but focus more on referrals than on direct, lasting relationships.

Like a dust cloud that nearly takes shape, it dissipates just as quickly—emerging in times of great need, led by those who recognize the gaps, only to fade away again.

The need is clear, yet the role of a matchmaker has never fully crystallized.

The pattern is almost always the same: relational work begins organically, driven by the heart, but over time, it becomes bureaucratized. In contrast, I’m advocating for the opposite—empowering those who address isolation yet feel constrained by structured systems to discover, embrace, and sustain the artful, relational work of social matchmaking.

The Matchmaker

While variations of matchmaking have been established in foster care, adoption, and romantic relationships, this role remains largely undefined for people with disabilities, the elderly, and other isolated groups who have long-term needs that persist into adulthood.

Without a clearly defined role, social matchmaking is treated as incidental rather than essential—leaving isolated people to fall through the cracks.

A man with developmental disabilities spends his days in a sheltered workshop, his growing depression unnoticed because staff focus on job skills, not personal connection. A young woman in a group home longs to take a dance class but has no one to accompany her. An elderly man in a nursing home goes months, even years, without a visitor.

In each case, formal services exist, but the relationships that create lasting change are missing. There are compassionate people who would gladly offer companionship—if only someone took the initiative to bring them together.

Building a Support Structure

To outline a framework for supporting matchmakers, let me first share the mission and then I’ll briefly breakdown the structure of the relationship-building program I founded and now lead.

Do For One is a relationship-building program that brings isolated people into greater community life. We selectively match one person with disabilities (‘Partner’) with another person who enjoys a more socially included life (‘Advocate’).

We then support voluntary advocates as they strive to understand, represent, and respond to the interests of their partner.

To accomplish this mission, we rely upon, resource, and support dedicated matchmakers through an established core leadership (our ‘Core Group’) which consists of paid staff, committees, board, community relationships, and more.

Your structure may look different, but the core idea remains: our program is built to uphold social matchmaking as a legitimate and vital role—one that carries a high calling. Social matchmakers are bridge-builders, fostering healing in a divided world.

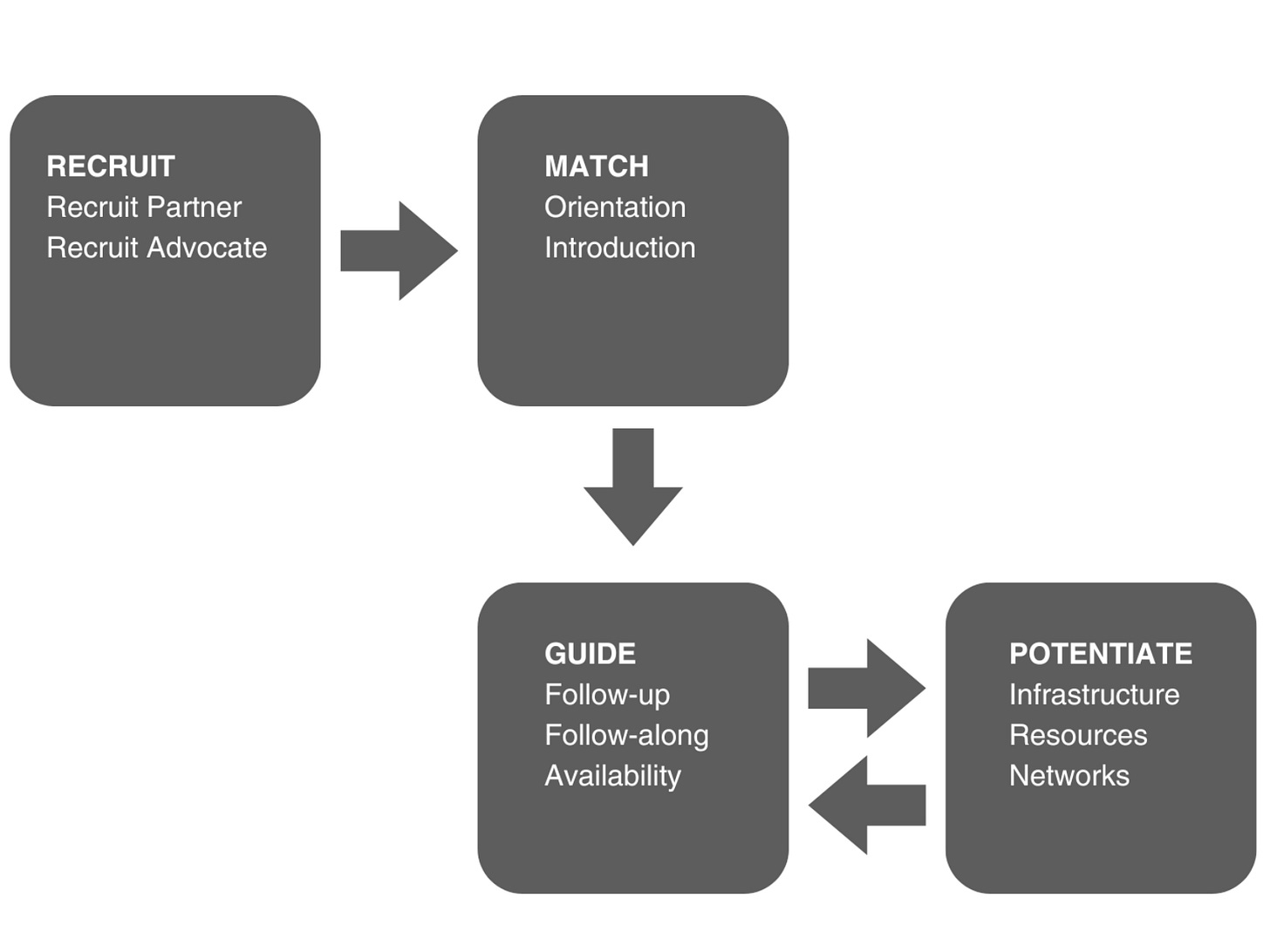

The Four Functions

A social matchmaker’s work is structured around four core functions, based on Citizen Advocacy—each essential for fostering meaningful and lasting relationships. To illustrate, I will revisit William’s story.

1. Recruiting: Identifying the Right People

Matchmakers don’t wait for people to come to them. They proactively seek out both Partners and Advocates. This means they engage with communities, forming connections with service providers and families, and building trust with those who have no one looking out for them.

After entering rehab, William lost his apartment. With no family to support him, he was placed in a nursing home permanently. The matchmaker recognized that what William needed wasn’t just services, but a person willing to stand beside him as an ally, a friend, and someone to help him navigate the process of regaining his independence.

2. Matching: Bringing the Right People Together

Bring the right people together is more than just shared interests—it’s about finding someone with the right mix of commitment, perspective, and capacity to accompany another person through life’s joys and challenges.

In William’s case, the matchmaker introduced him to David, a local retiree with a heart for helping others and experience navigating housing systems. On the surface, they didn’t have much in common, but the matchmaker saw David’s potential for persistence and William’s strong desire to regain control of his life.

3. Guiding: Walking with Relationships Over Time

Even the most promising relationships need support. The matchmaker remains involved—not by directing the relationship, but by offering encouragement, guidance, and problem-solving strategies.

For William and David, trust didn’t develop overnight. William had been let down before, and David needed insight on how to help without overstepping. The matchmaker provided regular check-ins, offered advice, and reminded David that his role wasn’t to “fix” William’s life but to be a steady, committed presence.

4. Potentiating: Fostering a Movement

Potentiating isn’t just about supporting individual relationships—it’s about fostering a culture where freely given relationships can flourish across societal barriers, creating an ecosystem of allies for lasting social change. This means equipping Advocates with tools, knowledge, and encouragement while also creating opportunities for them to learn from one another—fostering connections that can ripple into their communities and extended networks.

As William gained confidence, David became more skilled in advocacy. The matchmaker connected him with other Advocates, reinforcing that he wasn’t alone in his efforts. Together, David and William began working toward securing an apartment so William could leave the nursing home. The process is ongoing, but the momentum is moving in the right direction.

No matter what happens, David has committed to staying by William’s side. And they now have community who asks for updates, understands the situation, and even pitching in with their own ideas.

This is the power of social matchmaking. It’s not about one-time interventions or short-term assistance—it’s about cultivating relationships that restore dignity and belonging.

What Matchmakers Are NOT

Since this role is often embedded within other professions, it is frequently mistaken for social work or other direct-service fields.

🚫 We are NOT a social work agency.

We do not provide case management, therapy, or services to Partners.

🚫 We do NOT do advocacy or friendship on behalf of Partners.

Instead, we match Partners with voluntary Advocates and support those relationships.

🚫 We are NOT a referral agency.

While we may suggest resources, we do not exist to connect people with services, benefits, or professional care.

🚫 We do NOT file lawsuits or handle legal matters.

Partners may face injustices, but our program does not take on legal battles. Instead, we help Advocates recognize when outside resources or professionals are needed.

🚫 We are NOT a social club

Every event we host is designed to promote, educate, and strengthen freely-given relationships—not just provide entertainment.

Conclusion

When systems and government fail us—and they do, even now—it’s not policies that hold people together. It’s relationships.

What truly endures are the bonds of family and community. These relationships sustain us, especially in times of crisis.

This is why the role of the matchmaker is so vital—a peacemaker amid division. This role has long existed on the margins—unnoticed, informal, yet essential. It’s time to recognize the need, define the role, and strengthen its impact.

In my next post, I’ll outline some essential qualities of a social matchmaker—insights to help you identify and support those best suited for this work.

Additional resources:

Read More: Breaking Up Unplowed Ground: Forming a Core Group for Your Relationship-Building Program

In-Person Training: Lead For One | Do For One’s next Info Session

Email me: andrew@doforone.org